|

They consort in companies of three—a “front

stall,” a “back stall,” and a “nasty man.” . . . The “nasty man” is, of

course, the actual operator; and, accordingly, he is the leader in all

enterprises, and takes a larger share of the plunder. A regular gang does

not often make speculative ventures. They call that “throwing a chance

away,” meaning that they run extraordinary risks. Only when the rogues are

“hard up,” or made audacious by drink, or encouraged beyond their cooler

judgment by such a run of success as they have achieved in London lately,

do they “throw a chance away.” The favorite method is to select a promising

victim, mark his incomings and outgoings, and await a fair opportunity of

time and place. By many unsuspected means, as well as those which are open

to every body, they get to know that such and such a man carries a good

“stake” about with him, in money, watch, jewelry, etc., and that he is

generally to be found walking in a certain direction at certain seasons. He

is marked. Time and place are fixed for the deed; but opportunity is never

forced. If success appears doubtful on one occasion they wait till another

comes round, and will dog one man for nights and even weeks together. At

last fortune favors the unjust, and the thing is done. The “front stall”

walks a few yards in advance of the prey; it is his duty to look out for

dangers ahead. The “back stall” comes on at a still further distance

behind, or sometimes in the carriage-way-aloof, but at the victim’s side.

|

|

|

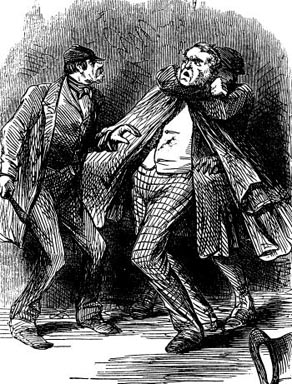

Immediately in his rear walks the “nasty man,” approaching nearer

and nearer, with steps which keep time with those of him whom he follows.

The first stall lifts his hat from his head in token that all is clear

beyond; the second stall makes no sign to the contrary; and then the

third ruffian, coming swiftly up, flings his right arm round the victim,

striking him smartly on the forehead. Instinctively he throws his head

back, and in that movement loses every chance of escape. His throat is

fully offered to his assailant, who instantly embraces it with his left

arm, the bone just above the wrist being pressed against the “apple” of

the throat. At the same moment the garroter, dropping his right hand,

seizes the other’s left wrist, and, thus supplied with a powerful lever,

draws him back upon his breast and there holds him. The “nasty man’s”

part is done. His burden is helpless from the first moment, and speedily

becomes insensible; all he has now to do is to be a little merciful. An

experienced garroter knows immediately when his prey is insensible (or so

he boasts), and then he relaxes his embrace somewhat; but if symptoms of

recovery should follow too rapidly the hug is tightened forthwith.

Meanwhile the stalls are busy. Their first care, after the victim is

seized and safely held, is to take off his hat and their comrade’s too;

hats awkwardly kick about in the scuffle, and it is obviously not well

for the garroter to leave any thing that is his on the field of strife.

This operation is assigned to the “front stall,” and is simple enough;

but he has sometimes to perform another and a far more onerous one.

Should the “nasty man” have a “tumble,” or, in language a little plainer,

should he find a difficulty in “screwing up” his subject, it is the duty

of the “front stall” to assist him by a heavy blow, generally delivered

just under the waist. The screwing up is easy after that, and then the

second stall proceeds to rifle the victim’s pockets. This done, the

garroter allows his insensible burden to drop to the ground, carefully

avoiding a fall, lest that should arouse him.

I once allowed a thief, . . . whom I visited in his

cell, to garrote me. We had a clear understanding that I was not to be

made insensible; but he explained that it was necessary that he should

screw me hard if I wished to experience the sensation of the garroted,

and to know how speedily the trick could be done. I submitted to this

view, and in a marvelously short period found that I had gone through

almost all that the “nasty man” inflicts in an ordinary way. The operation

was exactly what I have above described it; it occupied a few seconds

|

|

only; and yet, had I been held a few seconds longer, I must have

become insensible. As it was, I was wholly helpless, and my throat was

not easy again for several weeks afterward. Although this is the most

approved mode of garroting, there are others—as may be seen from the

police reports which have made the news-sheet so hideous lately; it is

obvious, moreover, that circumstances must sometimes oblige the

best-regulated gangs to vary their tactics.

|

|

|

|